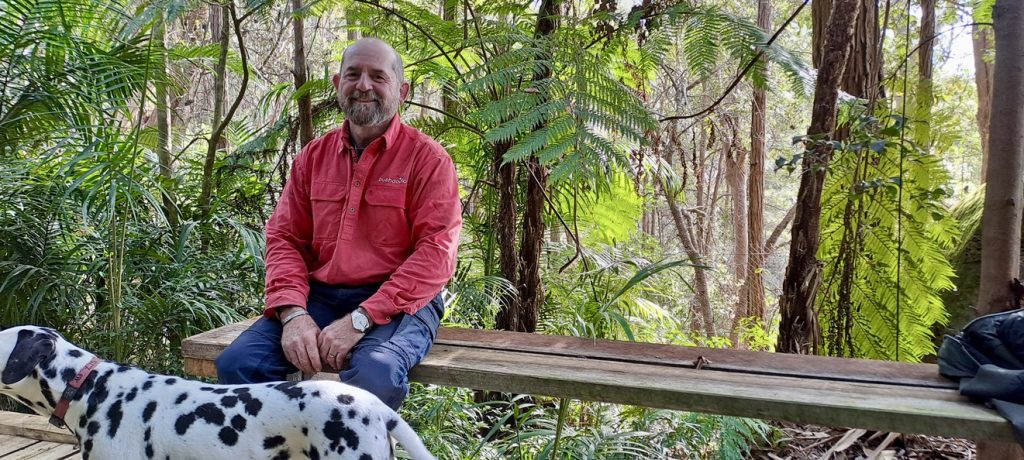

Shane in his garden oasis. (Hamish Dunlop)

By Hamish Dunlop

Planetary Health Initiative writer Hamish Dunlop speaks to Shane Grundy at Bush Doctor HQ. Shane explains how soft engineering techniques are helping rejuvenate swamps and improve water quality in the Blue Mountains. He talks about his bush doctoring journey and how he contributes to ecological restoration around the world.

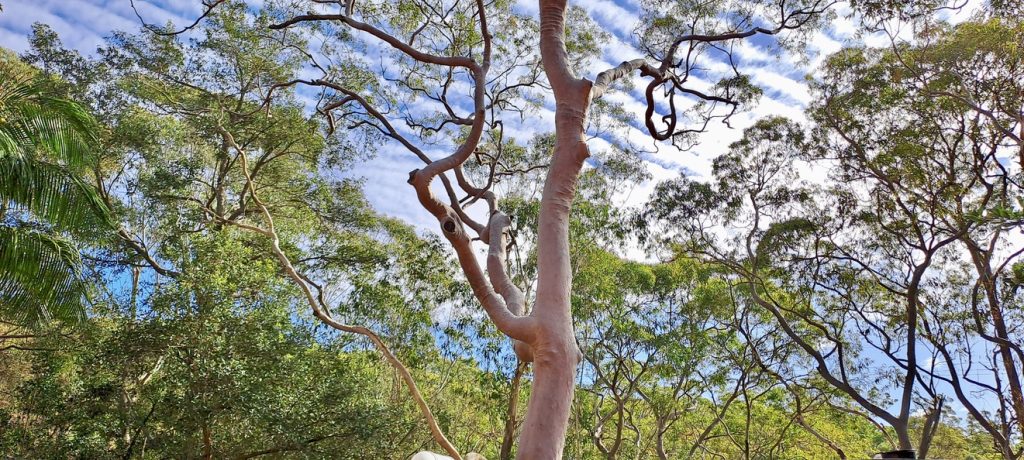

I’ve arrived at a property in South Springwood. Shane Grundy, aka the Bush Doctor is waiting for me at the bottom of the drive. As a mechanical arm rocks the gate open, a collie-cross and a dalmatian-cross rush out to greet me. Shane takes me upstairs to Bush Doctor HQ. Windows span across the north side of the building. They’re filled with blue sky and the beautiful twists and pink hues of an angophora. We’re about to sit down, but Shane suggests we take a walk around the garden.

The Angophora above the fern garden. (Hamish Dunlop)

We drop into temperate rainforest, lush with ferns and other rainforest species. It’s an oasis. Shane has planted many of these over the past 25 years. There are triangle and fan palms. A bromeliad wraps around the trunk of a coachwood tree. Shane points out a Davidson plum. In season, the fruits cluster on the stems. They’re a rich blue purple and reddish inside. “They make mad plum jam,” Shane says.

The Davidson plum with its thin trunk and serrated leaves. (Hamish Dunlop)

The garden is aesthetically beautiful, but functional as well. It manages the stormwater from two adjacent houses. Rainwater hits the hard surfaces such as the rooves and driveways. Some of it is stored in a water tank. The rest is directed into the landscaped garden. Sandstone-lined courses and rock basins slow the stormwater flow, giving it a chance to infiltrate into the ground. This process is something that Shane and his team construct on a much larger scale across the Blue Mountains using soft engineering techniques.

The sandstone-lined watercourse coming down from the basin. (Hamish Dunlop)

A love for swamps

Shane says passion is an over-used word, but he does love swamps. He values their natural beauty and their role in ecological communities.

“Swamps act like giant sponges that sit on the sandstone. They manage peak flows and support perennial creeks and streams. Many waterfalls in the mid and upper Blue Mountains such as Katoomba Falls and Wentworth Falls are fed by swamps in their catchments. They provide habitat for endangered species such as the Blue Mountains Water Skink and Giant Dragonfly. Upland swamps protect downstream vegetation and macroinvertebrate communities too.”

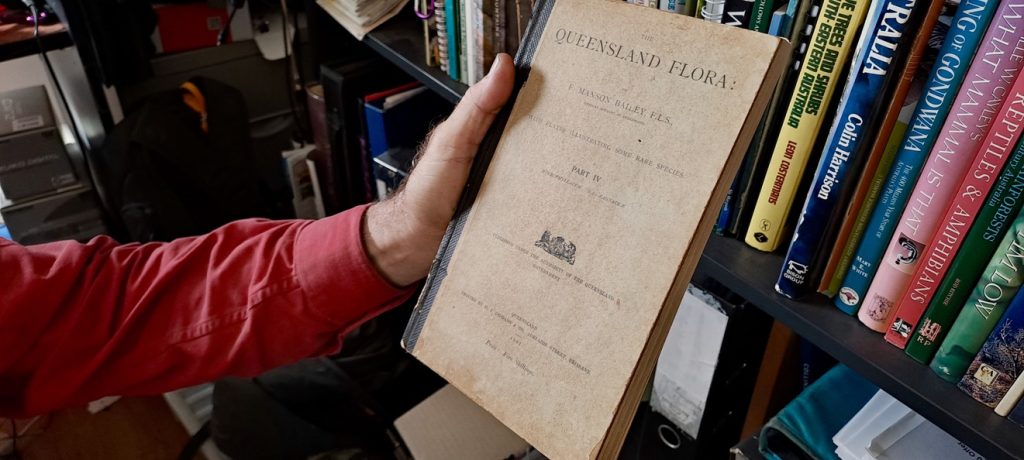

Shane with a few of his books. (Hamish Dunlop)

Swamps are important on a global scale. They are massive carbon sinks – the most efficient on the planet. Keeping carbon locked up is critical because carbon dioxide contributes to accelerated climate change. Shane tells me that three percent of the earth’s land is covered in peatlands. These include wetlands, swamps, fens, bogs and mires. They store an estimated 450 billion tonnes of carbon. The remaining forested land on the planet stores an estimated 300 billion tonnes. “You can see the value of the three percent.” he says.

Shane holding a copy of The Queensland Flora published in 1901. (Hamish Dunlop)

Shane explains the process of carbon release. “When swamps get damaged by erosion and drainage, they dry out and release carbon. The peat forming the spongy layer of swamps is vegetation – primarily the roots of sedges and rushes. As the peat grows, the roots stay behind. When swamps are inundated with water, there’s little oxygen to support the microbes that eat vegetation. The creation of carbon dioxide through vegetation consumption is limited. While there is some breakdown, this is far outweighed by the carbon that swamps store. This is why keeping swamps wet is crucial to all living things. Including us.”

Shane contributes to the health of swamps around the world through field research and consultation with the International Mire Conservation Group. He has travelled to places such as Malaysia, the Netherlands, South Africa, New Zealand and the Artic in Russia. Shane says, “The group is primarily constituted by scientists. A lot of them understand the science of peatlands. But when it comes to restoration, they may not know how to implement what needs to be done. My role on some of the trips has been to provide advice about practical implementation.”

A photo diary of Marmion Swamp

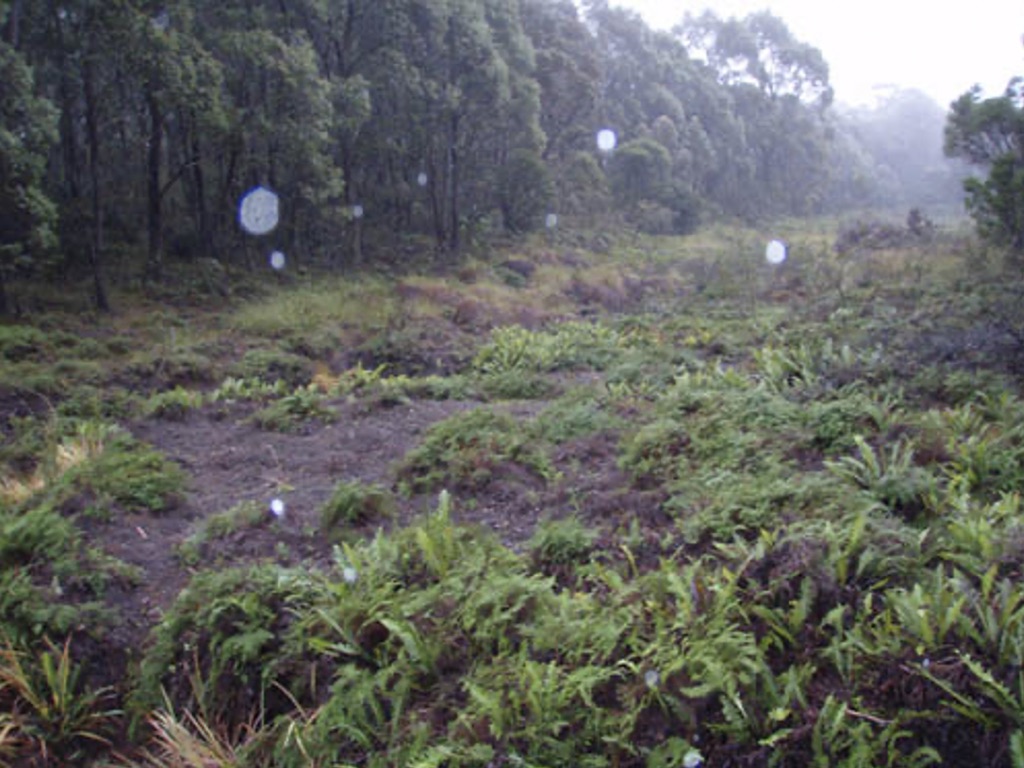

Marmion Swamp in June 2007 prior to restoration work. The dead ferns indicate the swamp drying out. (The Bush Doctor)

Marmion Swamp in Leura was the first swamp in the Blue Mountains to be restored using soft engineering methods. The techniques were introduced in a 2007 workshop hosted by Blue Mountains City Council. It was led by Roger Good and Geoff Hope, who pioneered the restoration of peat-forming bogs and fens in the Snowy Mountains, NSW.

Soft engineering employs tough but biodegradable materials such as coir logs and straw bales. It’s used to address erosion often caused by stormwater runoff. It does this by slowing the velocity of water and distributing its volume across larger areas. This leads to ‘rewetting’ and the return to healthy swamp functioning. Shane says it’s fantastic to see how restoration work compounds over time. The photo series shows Marmion Swamp from 2007 through to 2020.

Marmion Swamp in July 2007 after the commencement of restoration work. Coir logs, straw bales, jute matting, timber stakes and hardwood planks used to create water banks to slow and store water. (The Bush Doctor)

Marmion Swamp in July 2010. Returning fern growth. (The Bush Doctor)

Marmion Swamp in February 2020. A flourishing ecological community. (The Bush Doctor)

Wentworth Falls to Sydneysiders’ taps

Urban runoff from Canberra Avenue in Wentworth Falls is where the water starts its journey from landing on the earth, to coming out of taps in Sydney. It flows into Wentworth Falls Lake, then Jamison’s Creek. Entering Kedumba River, it continues down to Lake Burragorang, the source of Sydney’s drinking water.

Shane says, “The Wentworth Falls project was initiated by Blue Mountains City Council and Water NSW. Both organisations recognise the high environmental, cultural and social values of the Jamison Creek sub-catchment. The aim was to improve the quality of the urban runoff. We did this by building a series of sandstone-lined channels and biofiltration systems adjacent to Canberra Street. This protects people and the adjoining temperate highland peat swamp.”

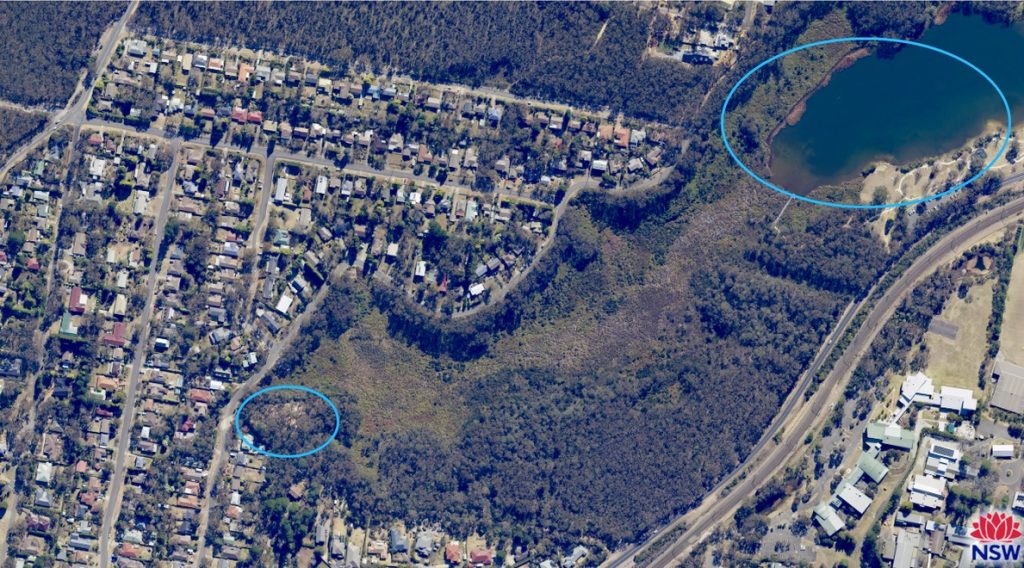

The first image shows the location of the biofilters with respect to the lake. The second image shows the Baramy trap (insert), the main channel and the diversions in and out of the biofilter basins.

The smaller blue oval denotes the location of the biofiltration systems while the larger oval indicates Wentworth Falls Lake (SIX maps).

Baramy trap, main stormwater channel and bio-basin locations (The Bush Doctor)

Shane explains that the Baramy trap has metal grids to remove larger rubbish such as plastic bottles. It captures sediment and larger biomatter as well. The waters feed into the biofilters and back into the main channel.

The biofilters are excavated basins. They are lined with geofabric, layered with gravel and sand. Sedges and rushes are planted around them. The plants and hard mediums support the filtration process.

The biofilters before planting (The Bush Doctor)

The same biofilter area today (Hamish Dunlop)

Litter, sediment, excess nutrients and pathogens are all filtered to varying degrees. The system slows water flow, facilitating groundwater recharge.

Shane and his team worked with Eric Mahony, Program Leader Natural Area Management at Blue Mountains City Council to design the biofiltration systems. Together they implemented these with the assistance of an earth moving contractor. Blue Mountains City Council’s Healthy Waterways Team has measured the water quality at the inflows and outflows of the biofilters.

Testing showed they removed on average 60% of faecal coliforms and suspended solids. A total of 30% nitrogen and 20% phosphorus were filtered out. Amy St Lawrence, Aquatic Systems Officer in the Healthy Waterways Team thinks the removal of coliforms happens simultaneously with the removal of pathogens indicated by those coliforms. “The biofilters remove pollutants from the stormwater before it enters the lake. This makes the water quality safer for swimming. The general recommendation is still to avoid swimming during and for up to 3 days following rain.”

Pop’s glasshouse

I asked Shane earlier in the conversation what led him to start The Bush Doctor (NSW) Pty Ltd. The story began in a glasshouse in Lidcombe where he remembers thinking how clever his Pop was growing elk and staghorn ferns on rocks. His connection with the natural world continued to be nurtured by spending time in the bush with his dad.

He’s subsequently made a career of caring for and learning from the land. He says one of the reasons for his commercial success was his ecological perspective – focusing on natural systems and relationships to facilitate positive restoration outcomes. Having spent an hour or two with him, I feel as if he’s a manifestation of this approach: someone who embodies the interconnectedness between human and non-humans worlds.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.