Joe and Merylese Mercieca at their passive home in Yellow Rock. (Hamish Dunlop)

Hamish Dunlop talks with Joe and Merylese Mercieca at Blue Eco Homes about the journey from a ‘fibromajestic’ home in Warrimoo to their newly completed Passivhaus in Yellow Rock. They discuss how sustainable design and building methods can support human health and the health of the planet, and reduce the risks of bushfire and extreme weather.

Key Points:

- The Mercieca’s have designed their home to reduce the risk of fire and extreme weather events.

- BAL-rated homes are less susceptible to ember attack, radiant heat and direct flame contact because of their construction.

- Water availability is maximised with a 120,000L water tank buried under the firepit circle; grey water for the garden; and black water treated by a Fuji Clean waste management system. It uses a combination of anerobic and aerobic bacteria and mechanical digestion processes.

Share this article:

Coming out of the cold

It’s a relief to come out of the cold into Merylese and Joe’s Yellow Rock home. It’s a beautiful space filled with warm tones and the textures of natural materials. I’m conscious of how unobtrusively comfortable it is. There are no drafts or sounds of air circulating. Compared with the winter climate outside, the temperature and humidity make breathing effortless.

This is certainly true for Joe. After a lifetime of exposure to dust and chemicals in the construction industry, he has developed occupational asthma. Until recently, he coughed constantly and used an asthma puffer. He says that after two or three months living in the Yellow Rock house, the cough disappeared. He doesn’t use the puffer anymore either.

The Winmalee House: A journey to health and sustainability

When they started their family, Joe and Merylese lived in a house in Warrimoo. They called it ‘The Fibromajestic’. Merylese says the kids were getting asthma and croup and Joe’s occupational asthma wasn’t good. It wasn’t a bad house she recalls, “but we did ask ourselves the question, ‘What’s going on here?’” The answer led to designing and building their own sustainable, high performing home in Winmalee – one that far exceeded the requirements of the National Construction Code.

The Winmalee home next to the business office and garage (out of view). (Blue Eco Homes)

The Winmalee home was better for the family’s health and BAL fire-rated. BAL-rated homes are less susceptible to ember attack, radiant heat and direct flame contact because of their construction. It is BAL 29 on one side and BAL 40 on the other. The scale ranges from BAL LOW to BAL 40 with BAL FZ (Flame Zone) being the highest rating.

The house survived the 2013 Winmalee fire, but because of the intensity and proximity, the cladding and the insulation had to be replaced.

The Winmalee house that survived the 2013 fire next to the office that didn’t. (Blue Eco Homes)

A Passive Home in Yellow Rock

The Yellow Rock house: three-in-one. (Blue Eco Homes)

Their current Yellow Rock home was completed in 2021. In addition to constructing it as a passive and BAL-rated house, other decisions make wellbeing a holistic practice for Joe and Merylese. They only use chemical-free Enjo cloths and the occasional splash of vinegar to clean. Beds and couches are made of non-synthetic materials and fabrics. According to Joe and Merylese, all of this contributes to an irritant-free environment that has helped Joe’s occupational asthma and the family’s health generally.

The cloths Joe and Merylese use for chemical-free cleaning. (Hamish Dunlop)

Joe tells me they built the house with family in mind. “It’s really three houses in one. Merylese and I live on the central floor and one of our children and her family live upstairs. We have the downstairs available for when our parents get older, or when friends might need it.” He says it’s a house built to last multiple lifetimes, that will provide a high-quality living environment for generations to come.

The house has a 120,000L water tank buried under the firepit circle. Grey water is used to water the garden. Black water is treated by a Fuji Clean waste management system. It uses a combination of anerobic and aerobic bacteria and mechanical digestion processes. The effluent is pure enough to be discharged above ground. It’s sprayed on the garden and lawn at the back of the house.

Unobtrusive Fuji Clean water management system (green, middle, slightly left of centre) and the gardens and lawns that benefit from its processed effluent. (Hamish Dunlop)

Joe grew up camping in the bush with his family and exploring the outdoors through Scouts. He recalls his dad collecting grey water from the washing machine and shower to use on the garden before ‘sustainability’ was a buzz word.

Merylese worked as a clinical nurse consultant in respiratory medicine before joining Joe at Blue Eco Homes in 2010. She never thought her journey would come full circle; building houses that directly address the quality of air homeowners breathe.

Passivhaus, or passive houses

Passive homes have been built in Europe for some time, but they are relatively new in the Australian landscape. While they are significantly more expensive than built-to-code homes upfront, they provide a range of ongoing benefits.

Passive homes are airtight and have Mechanical Heat Recovery Ventilation systems. MHRVs constantly draw air from outside and expel stale air, while keeping the temperature and humidity constant. They use very little energy, are noiseless and recover heat when the weather is cooler than the desired internal temperature. Passive houses also have insulation appropriate for the climate zone, good quality windows with double or triple glazing and no thermal bridges that allow heat to travel through the walls.

The Mechanical Heat Recovery Ventilation system at the Yellow Rock home. (Hamish Dunlop)

This makes the home environment comfortable and has significant health benefits. Excessive cold or heat are responsible for an average 2% of deaths nationwide, rising as high as 9% in hot climates and 3.6% in especially cold climates such as the Blue Mountains. Poor housing more generally leads to negative mental and physical health outcomes. Condensation and mould can contribute to respiratory illnesses. In passive houses, mould growth is inhibited through the elimination of condensation while pollens and other irritants are filtered out.

Joe opening one of the triple glazed windows. (Hamish Dunlop)

Merylese says people sometimes ask what happens in a blackout if there’s no power to run the ventilation system. She says you’d be hungry for some time before you ran out of air. “You can also just open the windows like in any other house. We have a client who loves having her windows open. That’s how they’ve chosen to use their home. But when they want to, they can just close them up and the house brings itself into balance.”

Healthy homes case study

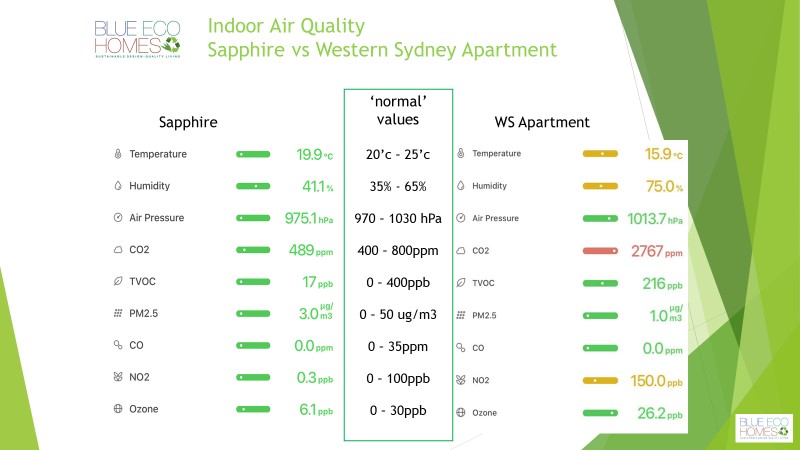

With a background in respiratory health, Merylese was interested in quantifying the benefits of passive verses built-to-code houses. Using air monitoring equipment, she compared their 2019-completed Sapphire show home, to a new unit in Western Sydney.

Slide comparing the two homes (Blue Eco Homes)

The results above are indicative of the differences, although the extremes seen in the Western Sydney apartment were not constant. The values were viewable in real time on a mobile phone app and alarms were triggered when values fell outside the normal range.

The app showing real-time data about air quality at the Sapphire show home. (Hamish Dunlop)

Merylese says that on several occasions she called the apartment owner to tell her some of the levels were particularly high. “At one stage the carbon dioxide level reached 4000ppm, when the normal range is between 400 and 800ppm. That’s enough to start making you feel drowsy. The nitrogen dioxide levels tended to spike when cooking was taking place. When it’s cold, you don’t want to open the window, but in a standard build, that means vastly reduced air quality.”

Lobbying to improve the National Construction Code to improve people’s health

Merylese tells me the National Construction Code 2022 was the first iteration in nine years to include major changes. She and Joe hope the code will continue to move towards the passive home standard. “The next review is in 2025 and then 2028. In this most recent update, buildings are required to be more airtight. This is progress, but without mechanical ventilation it could lead to humidity and air quality issues.”

They have spoken with Trish Doyle and Susan Templeman about the quality of social housing. Merylese says there was general agreement that building social housing to passive house standards would be a good thing. “It’s not just about business for us.” she says. “Houses and health and wellbeing are tied together. Both Joe and I are committed to the development of healthier and more sustainable homes.”

Sustainable homes, sustainable business

Joe and Merylese build resource-sensitive homes. Their business embodies the ethos of sustainability too. They have a waste management system that ensures 94% of the business’s waste is either reused or recycled, with the national average just 55%.

Merylese has a Certificate 4 in Carbon Management and produces the business’s carbon assessment. They use EcoProfit, a Blue Mountains-based carbon accounting business to reach net zero status. She says EcoProfit brings the benefit of the carbon economy back to the local community. The company gives $1 for every carbon credit it purchases to the Sunshine Project charity. Sunshine funds Blue Mountains solar installation projects. It enables community organisations to reduce energy-related emissions and to be more self-sufficient in times of disaster.

Future proofing human and planetary health

Passive houses are currently out of many people’s reach financially. It would be easy to discount them as ‘luxury’, especially given the cost-of-living crisis and the deficit of social and affordable housing that currently threaten many people’s right to having a home.

While we do need to directly address the housing availability crisis, it’s worth thinking about housing as one point on the wellbeing scale, not an end. Merylese and Joe have demonstrated some of the ways that it’s possible to reduce negative impacts of poor housing on human health and deliver positive longer-term outcomes for people and the planet. It should be possible for government, organisations, businesses and communities to keep these principles in view.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.