The artists (from left to right) Paul Rhodes, Annette Coulter, Martin Roberts, Clare Delaney, Jo Davies and Tim Newman. (Hamish Dunlop)

By Hamish Dunlop

Six Blue Mountains artists take strikingly different approaches to expressing ecological emotions associated with fire, flood and pandemic. The members of the group are psychologists, art therapists, counsellors and emotion-sensitive practitioners. The exhibition reflects their experiences and their clients’ experiences of recent disasters.

Tipping Points showcases work by six Blue Mountains artists who experienced the fires, floods and pandemic of recent years. The artworks explore psychological impacts of these disasters on the artists and the community. Most are practising psychologists, art therapists and counsellors, so the group members are uniquely placed to respond to the experiences of the people they work with professionally, as well as explore their own lived experiences.

Paul Rhodes, artist and Associate Professor of Psychology at Sydney University said, “Psychologists and therapists are a barometer of what our community has been through. We’re listening to their grief, their pain and their suffering. We’re also seeing their recovery, their strengths and their resilience. The works in this exhibition explore all these ecological emotions.”

Paul says we often think about emotions as internal, subjective and personal. “Climate emotions are completely different. They are collective and transpersonal, arising out of shared experience. They are also relational, emerging out of the connections between people. And between people and the rest of the natural world.”

Art therapist and psychotherapist Annette Coulter and Paul were instrumental in bringing the exhibition to life. They have known each other a long time. Over coffee they decided something had to be done to help themselves and the community to engage with ecological emotions.

Annette says, “Artwork can help us to come into a different relationship with internal experiences. This objective distance and the aesthetic qualities of the artwork can speak to trauma and difficulty and open us to moments of beauty and renewal.”

The artists use materials and processes that resonate with emotions associated with the themes of disaster. Fast drying alcohol inks reactivated by drops of isopropyl alcohol behave in unpredictable ways. Natural phenomena such as wind, or the human act of tilting paper further enmesh materials, time and artistic intentions. Incidental marks are taken as avenues for exploration, rather than mistakes to be corrected. Materials such as bitumen and shellac intertwine chemically. As substances contaminate each other, they infect meaning in the process.

Each artist’s work is distinctive, but collectively, they bring ecological emotions into a shared space. This is an important part of addressing emotions that have come from outside us. Paul explains:

“Because climate emotions are generated through ecological relationships, it makes sense that both human and non-human actors are involved in the production and maintenance of healing effects. The human and the koala and the tree are all suffering together. If we can recognise this and decentre our minds, we can become an egalitarian partner with all living beings.”

Paul Rhodes: between ‘hopism’ and denial

Paul with his work ‘Self-Portraits, Post-Human’ (centre). (Hamish Dunlop)

Paul works in the Clinical Psychology Unit at the University of Sydney. He is also a member of the Sydney Environmental Institute, where he researches ecological emotions, feelings and affects. Paul thinks that emotions are culturally and ecologically produced, rather than being solely internal personal matters.

“We’ve had this very limited view of what emotions are from a very conservative field of psychology. But think about the bushfires. For the first time in my life a client said to me, do you live in the Mountains? Are you okay? I’ve never had a client reach out to me before as a therapist, you know? It was an interesting dynamic, because I realised, oh my god, we share all of this.”

As part of facing climate change, Paul says we mustn’t deny environmental degradation, or fall into ‘compulsory hopism’. He uses religious imagery, colour and humour to examine difficult physical and emotional realities such as grief and trauma. “It’s taboo, but these things need to be part of the community discourse.”

‘Rapture’ by Paul Rhodes. (Hamish Dunlop)

In Rapture, the warming sea melts the ice, the whales turn tail-up and die, while people blissfully ascend to heaven. The work is less about religion and more about the dangers of a human-centric world view. In Self-Portraits, Post-Human, he imagines himself as a spirit creature, carrying men in black suits around the world. As an embodiment of all living things, the creature seeks to reveal the destructive force of unbridled capitalism.

‘Background Factors’ by Paul Rhodes (detail). (Hamish Dunlop)

Many of Paul’s artworks have a dystopian bent and he believes we should not hide our more challenging emotions. He also thinks that staring into the face of climate change is not sustainable. “Looking away is not denying the reality. It’s knowing you are purposefully putting it aside, because you can’t think about it anymore. That’s different from denialism,” Paul says. “Sometimes you need to park things and get on with your life and that’s helpful. That’s the middle.”

Jo Davies: the permeability of bodies

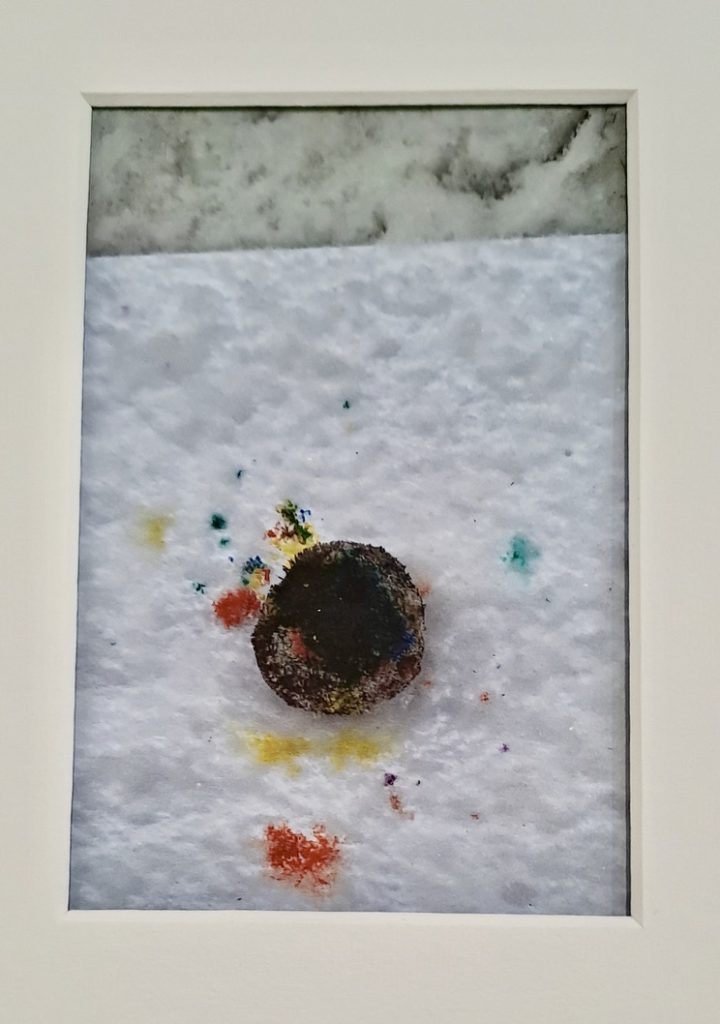

‘Snow’ by Jo Davies. (Hamish Dunlop)

Jo Davies is an artist, art therapist and counsellor. She says her artwork explores the movement of substances and energy between bodies. Through fires, floods and the pandemic, boundaries between us and the outside world have blurred. Viruses got under our skins and smoke infiltrated our lungs. In Snow, Jo explores how all living and non-living things are connected. Her process involves being sensitive to the relationship between materials, bodily actions and the time-based effects of snow, wind and water.

‘Snow’ by Jo Davies. The first print in the series. (Hamish Dunlop)

Snow is a series of nine glicee prints that document her process of co-creating with nature. Following a chance snowfall, she placed a piece of paper on the lawn in her backyard. When snow had covered it, she placed a sponge, inked with a variety of colours on top. Over the next three days, she took a serious of photos. These documented how the water-based inks, the natural elements and paper became entangled.

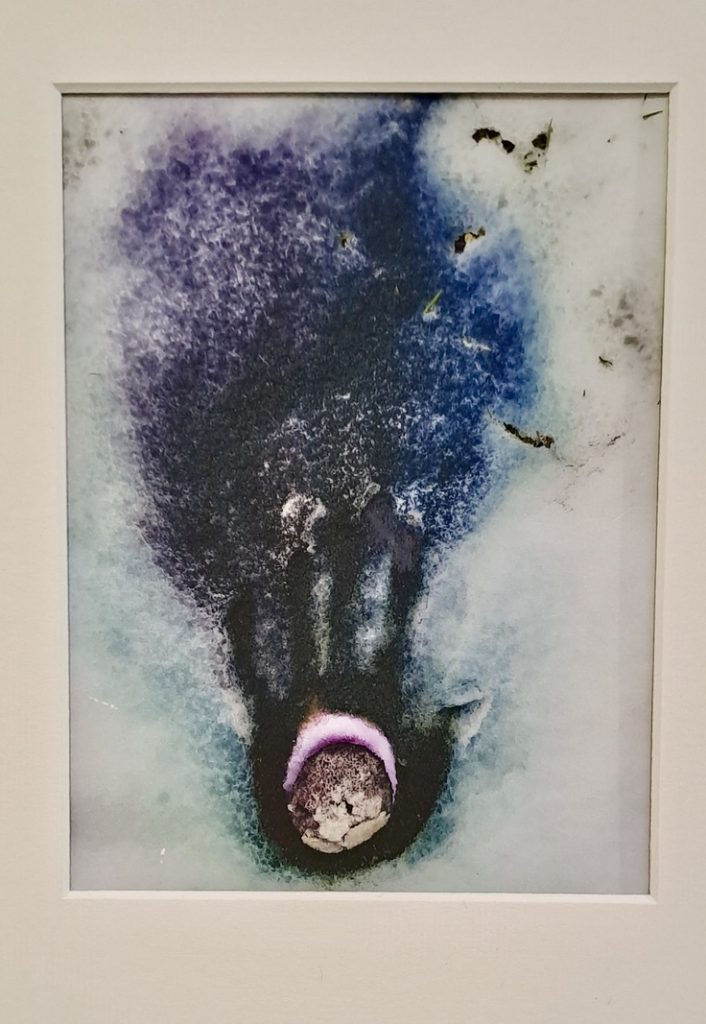

At one point, she used her hand to press down on the sponge. This physical process integrated her thinking, feeling and sensing into the ebbs and flows of natural processes. “It’s about noticing,” she says. “Watching the ink stain my hand and enter my body. Noticing how it runs into the earth.”

‘Snow’ by Jo Davies. The sixth print in the series. (Hamish Dunlop)

“You might think this is ephemeral art, because it comes and goes, but it’s not. This is because everything goes somewhere else and becomes something else. I’ve been coming into a deeper understanding of this through my artistic process. Becoming mindful that whatever I do in my interactions with the world, it’s going to change something.”

Annette Coulter: the aesthetics of unpredictability

Annette with her work ‘Infection’ (left). (Hamish Dunlop)

Annette says she’s trying to express different emotional states that occur when people deal with crisis and disaster. It’s a therapeutic process for her and she thinks the artworks can help the community too. But she’s not trying to communicate a particular message to the viewer. “What it means to me can be different to how it strikes someone else.”

She works abstractly and takes advantage of accidental marks – ones that arise outside the artist’s direct intention. The alcohol inks Annette uses support this way of working. They dry fast but can be reactivated and manipulated by applying isopropyl alcohol. Drops from a bottle, tilted paper, blowing ink solutions with a straw, or using a brush can result in varying effects. These are often organic in nature and application techniques can produce unpredictable and unexpected results.

Detail of ‘Infection’ by Annette Coulter (Hamish Dunlop)

In Infection, Annette used these qualities to explore contamination. Starting with pure blue ink in the centre of the artwork, she layered different colours and forms. The inks are contagious by nature, and she guided their application using her aesthetic sensibilities. The result is visceral and beautiful.

Annette says that beauty plays a role in how the artwork can help the community. Seeing themes such as infection externally represented can be challenging, especially if they’ve impacted your life. She thinks the aesthetic component of artworks that address difficult emotions can assist people to internally disengage. “Through the externalisation of emotions and beauty, you can get a bit of reflective distance.” she says.

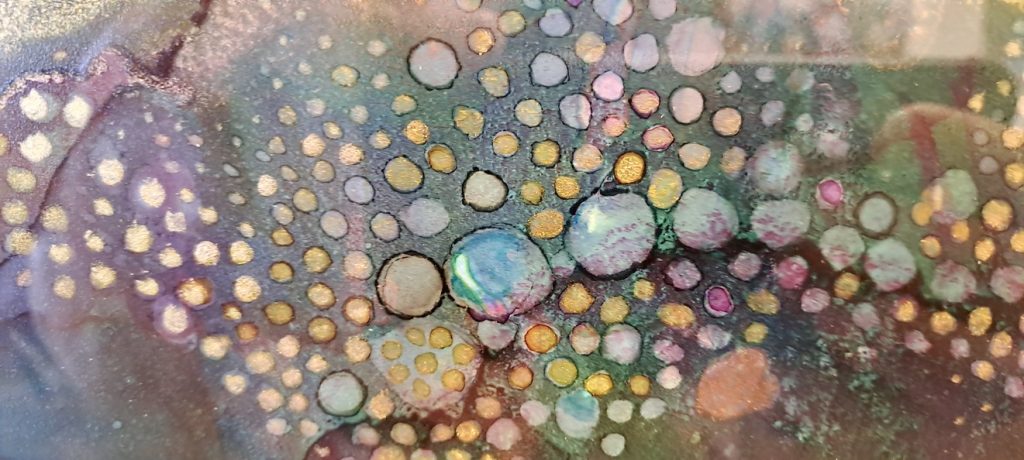

Detail of ‘Emerging Jewel’ by Annette Coulter (Hamish Dunlop)

Emerging Jewel is a more optimistic artwork: something rich and positive rising up out of a sea of jaggedness. Again, it’s a work of many layers. Annette says it’s one she really likes. “A lot of work went into this one.” She tells me she doesn’t spend much time contemplating the artworks she creates. “It’s all in the making.” The physical artworks themselves are not of primary importance. Rather, it’s the emotional galaxies she traverses in their creation.

Tim Newman: the matter of optimism

Tim Newman, with his work ‘Dark Matter and Optimism (I)’ (Hamish Dunlop)

Tim Newman’s Dark Matter and Optimism (I) layers the emotional experience of disasters with the light and movement of optimism. He says the paradox of not being able to do anything about war, climate change and pandemic, is that you have to maintain a level of optimism to change anything at all.

The name of the artwork comes from a conversation Tim had with his son’s father-in-law. He told Tim about a friend who was trying to win a Nobel Prize in astrophysics for dark matter research. He though his friend was a bit optimistic. This blending in language of the ideas of darkness and optimism, was a perfect fit for an artwork exploring the relationship between two intertwined emotional imperatives.

Tim used a variety of media to create the artwork including shellac, bitumen and gouache. Gouache is an opaque water-based medium laced with natural pigments, while bitumen is a sticky black form of petroleum. Shellac is refined from resin secreted by female lac bugs in the forests of Southeast Asia. The way these substances folded in and out of each other, reacting chemically after Tim’s repeated applications and layering, is where process meets meaning.

Referring to the darker colours down the bottom half of the painting, Tim tells me he used an electric sander to wear some of the darkness away. Not to remove it, he assures me. The sanding exposes more layers, revealing a complexity of emotion, wrought through colour, texture and luminosity.

Tim Newman’s ‘Dark Matter and Optimism (I)’ (detail) (Hamish Dunlop)

Martin Roberts: the alchemy of meaning

Martin with a selection of his artworks. (Hamish Dunlop)

The Black Summer fires of 2019/20 felt like a tipping point for Martin Roberts. There were months of smoke as the fires got closer and closer. It was a moment in time where physical and psychological thresholds were crossed in ways that Martin doesn’t believe can entirely be undone.

Martin says it can be hard to express the experience of being so overwhelmed. As an art therapist and counsellor, he believes that art is a way to express these complex emotional states and come into a different relationship with them.

His artistic process involves a wide range of materials including wood, alcohol inks, organza, plastics and found objects. In Highway (far left in above image), Martin took materials and transformed them in the same way the fire did. He burnt wood in his back garden and melted plastic from a chocolate box tray. He says, “The process took over, but it got very messy – my studio was a disaster zone. Bits of burnt wood and melted plastic and an acrid smell in the air.”

Creating Highway combined unpredictable and alchemic processes with considered construction. He cut precise slots for the burnt wood to make it sit flush with the other components. To represent a fiery haze, he carefully cut, stitched and stretched organza over cut-up plastic folders and alcohol inks. The external re-organisation of disaster-related elements plays a role in transforming internal emotional landscapes.

Martin says that despite his intentions, the way materials interact with each other is aesthetically unpredictable. “In a way, it does what it’s going to do. I have an idea, but the artwork takes on a life of its own.” He tells me he hasn’t had time to look at the artworks he’s exhibiting properly. “Some of them were only finished days before the exhibition’s opening. I’m looking forward to the opportunity to take them in.”

Clare Delaney: for the love of compost

Clare with her work ‘Fragile’.(Hamish Dunlop)

Over the past 20 years, Clare Delaney’s backyard has transformed into a flourishing vegetable garden. At the heart of this garden is compost. Clare says, “I love compost. I love the aliveness of it. How the soil creatures turn scraps from the kitchen, or garden detritus into rich, beautiful matter.”

She is acutely aware of the impact humans are having on the natural world. Feeding the soil is one way she gives back. Her artistic process is informed by finding what sits comfortably with her heart. She confesses that she experiences some cognitive dissonance: wanting to look after the planet, but still driving a petrol-fuelled car. Wanting to have a light artistic footprint, but still painting with some acrylics and oils.

Her work Fragile reflects a move towards a more sustainable art practice. It is a collaboration between human and non-human worlds. She remembers when she first pulled something out of the compost bin and thought, “Wow. Isn’t that wonderful!” Quickly followed by, “Hold on. Can I?”

She started putting scraps of canvas, bits of cardboard and old paper table clothes into the compost bins. Sometimes they would stay there for months. She might pull them out at times, cover them in coffee grounds and weeds and leave them on the deck to weather. It’s a delicate balance: left too long and the paper would dissolve. Over time, she collected a series of human-compost art samples. These also contained pieces of plastic and fruit stickers that had made their way into the mix.

‘Fragile’ (detail) (Hamish Dunlop)

Fragile is composed of these samples. Clare initially stuck them onto flattened cardboard boxes. They were going to be a boat, one that could carry the whole world. But the half circle became a sphere – an archetypal shape Clare says humans have always been drawn to. She dyed the exposed cardboard black with water-based ink and used old bandages to create a distinct edge. It wasn’t until afterwards that she realised the force of the metaphor: our need to care for mother earth.

The last (hopeful) words

As I come away from Tipping Points, I find myself thinking about my own ecological emotions. I think about denial and hopism as two ballasts. Is it possible that instead of being treacherous places to fall into, they frame a middle ground?

I feel how together we are in this place: the forces that affect human emotions, also affect the more-than-human world. We are all living in times of disaster, so let’s shake one another with art and actions and words that reverberate across living and future generations. Let’s be mindful too, for quiet spaces are required to settle troubled waters.

Tipping Points is showing at the Braemar Gallery until 2nd July.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.